My watch alarm sang a gentle tingle. I quickly silenced it. I was already awake.

I lay in bed, warm under the Maasai blanket except for my nose. It was sticking out from my blanket bunker so I could breathe, smelling the cold wind, carrying smells of dew and nature and fire.

A much louder alarm sounded. Molly, a few feet away in her bed, turned over to silence it.

It was marathon day, in Kenya. We’d be running Lewa Marathon with the fastest people on earth.

“Ready?” I asked her, in the darkness.

“As I’ll ever be,” she said, her British accent surprisingly alert for 5:00 a.m. She’d been lying in bed since 3:00 a.m., unable to sleep; her husband had sent her a text message from Spain that morning, waking her up.

About seven months ago, I was running hills one morning as a training exercise. I tweaked something in my right knee on a steep downhill. I deserved it; just moments before, someone had warned me to take the downhills easy, and I had cavalierly ignored him. However, since then, I’d not run more than eight consecutive miles – the knee pain was unbearable. My last “long run” before coming to Kenya was maybe a 5k (3.1 miles) in March, along with a few more just a few days ago. I ran a total of seven miles on Wednesday before the race. That was it.

The doctors didn’t know what it was. We’d cycled through several different diagnoses, each more ridiculous than the last, culminating in a suggestion of surgery, which I’d avoided. So, I had no idea how my knee would hold up for 26.2 miles. In my mind, I figured I’d maybe get a 10k pain free, then have to hobble the rest. As long as I finished the half-marathon before the 3:10 cutoff, I’d be okay.

It wasn’t like I hadn’t been working, however. I’d been spinning and climbing stairs every morning for at least 90 minutes, and up to three hours for the week before leaving. Physically, I was in good shape. I just hadn’t done any real running.

Within moments we were bundled up in jackets and had unzipped the tent flap, stepping out into the darkness. The moon was outshining most of the stars, but the Milky Way was just barely be visible in the dark blue sky. We made our way across wet, sharp African grass to breakfast.

Already, runners were quietly standing around the campfire, or sitting on wood couches with red plaid pillows. We were nervous waiting for breakfast, anxiously shifting our weight back and forth as we held our coffee mugs, trying to keep our fingers warm. It would be close to 90 degrees later that morning, but for now, we were freezing.

When breakfast appeared, we bolted down breakfast of toast and crepes, avoiding anything that might be spicy, resemble a vegetable, or have something in common with a heavy meat. We hurried back to the tent. Molly and I changed into our running clothes, which we had laid out the night before. At 6:15, we assembled with the other runners in our group, took a team picture in the dawn light, and walked to the start line.

Runner’s World Magazine included the Lewa Marathon in it’s list of ‘top ten races to run in your life’ The race is in the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, a game part home to quintessential African wildlife, like lions, elephants, rhinoceros, hyenas, cheetahs, and cape buffalo. There are no physical barriers between runners and the wildlife. Security patrols with AK 47s patrol the course to keep the animals away from the runners, and two helicopters and a spotter plane continuously circle the course to prevent animals wandering on to the course.

The race is difficult. The two loops are run on a rolling red dirt road, which usually acts as a four-wheel drive trail for safari vehicles. The average course elevation is just over a mile above sea level. And, as the race is within 100 mile sod the equator, the beating sun can bring afternoon temperatures as high as 90 degrees Fahrenheit.

The fastest marathon ever run was in about two hours and three minutes. On this course, it’s about two hours and twenty minutes. That’s 11% slower. This is not an easy course.

The scene was classically African. The sun was just coming up behind the silhouetted umbrella acacia trees, casting a gentle orange glow across the grass. All that was missing were the elephants.

As we made our way to the start line, we mzungus (white people) felt somewhat intimidated. Every so often, a small herd of tight, fit, skinny Kenyans would sprint by in matching track suits. They were so fast, they were overtaking cars. For them, it was just a warmup. Probably they were jogging.

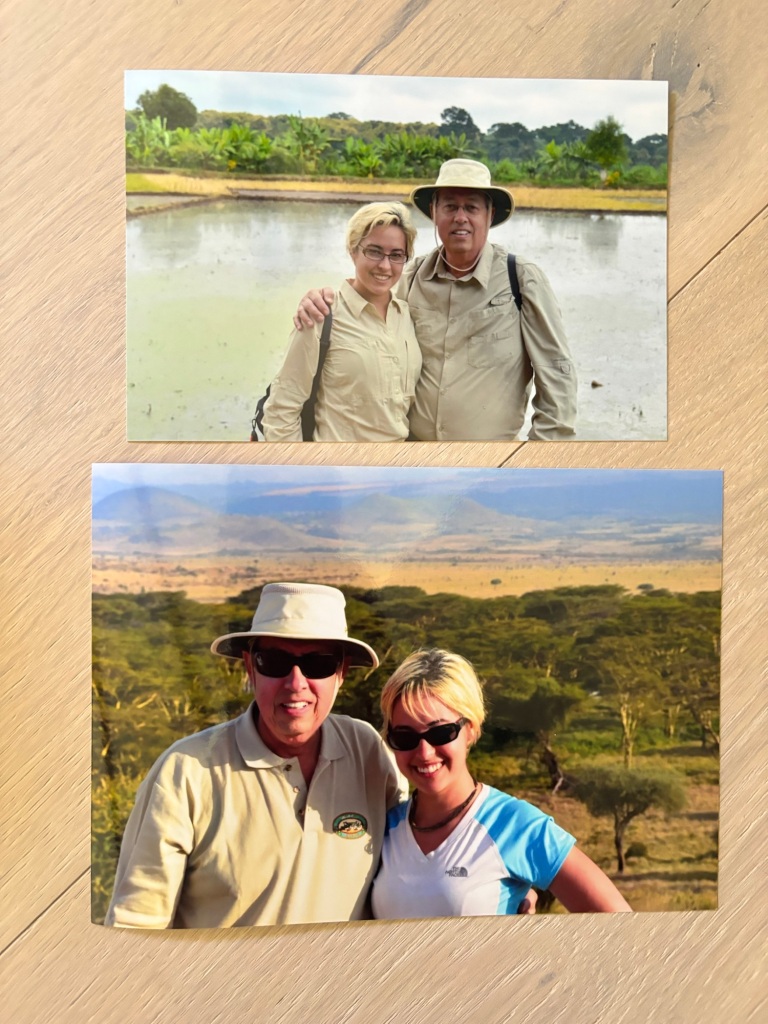

We stripped off our outer layers and handed them to Dad, who had volunteered to be the unofficial race photographer and crew for our group. By the end of the day, he’d taken somewhere around 1,000 photos of our team. Somewhere along the way, he’d earned the nickname “Papa Safari.”

About 1,200 runners would be out on the course today. About 1,000 of them would be running the half marathon. The second lap would be quite lonely for the approximately 200 of us running the full marathon.

As the hour drew nigh, we funneled into buckets by gender – men on the left, women on the right. A line of neon-yellow-clad guards acted as the start line. Tiny Kenyan girls, smiling with nervousness I could identify with, crushed up against them. We all had energy to burn, and were about to get the chance to do it.

Molly and I caught eyes – she was up front with the fast Kenyans, and looked elated. She was gesturing wildly at the runners, her eyes light with excitement. Her goal was to beat at least one Kenyan, and she was primed to do it. I was several lines further back; I had no pretensions of coming even close to a top time, and figured that I might even be lapped by some of the speedier Kenyans at the end of my first half.

I was nervous. I’ve never been so nervous before a race, and this was only a marathon. I hoped the knee would at least get me to 10k pain free.

We counted down to the start. The seconds seemed so far apart. It made me understand why “African time” was always a half-hour late; their seconds were so much longer than normal seconds.

The yellow guards sprinted ahead and dispersed. The front runners took off. I broke into a leisurely jog. My plan for the day: start out slow and end slower.

In America, cars drive on the right side of the road. Faster cars pass on the left. This is true of runners, too; runners always pass on the left.

In Kenya, cars drive on the left side of the road, and overtake on the right. I spent the first 5k trying to figure out what side everyone was passing on. It seemed mixed. I eventually decided that, being in Kenya, I would pass on the right, and ran through my fair share of tall grass while passing up slower runners. I also got passed as well – that would be a common theme for the rest of the day.

After mostly navigating the early stampede, I tried to settle into a reasonable pace. I also kept checking my watch to see how many minutes I’d run; usually I could feel my knee around 17 minutes, and by 24 minutes the pain was unbearable and I was reduced to a walk. But the minutes ticked by with the kilometers, and I felt no pain. My pace was slow, but also not crawling.

The first lap was easy. There were aid stations every 2.5k, which is very often – most races have them every 5k or 5 miles. The hills seemed easy too. I felt slow, though; a combination of a lack of running training and the altitude made this race difficult.

The scenery was gorgeous. The trails were so well maintained, which runners really care about. They were wide and flat, and alternating between iron-rich red dirt and volcanic black dirt. The grass was about chest-high, undulating into the mountains in the distance. Umbrella acacia trees spotted the vast expanse.

On the first lap, I found several of the runners on my team – mostly they were passing me. One of the women in my group, Cara, came up behind me around the 15k mark.

After the preliminary obligatory banter, she said, “I’m setting two PRs today!” (PR stands for “Personal Record.”

“What?!” I panted out between breaths, impressed.

“Yep!” She exclaimed. She stopped by the side of the road to take a quick photo of a herd of zebras, then caught up again. “Slowest half marathon ever, and most pictures taken during a half marathon.” She grinned, then took off again, to find another photo opportunity.

On a hill to the left, a very large herd of elephants were grazing. There must have been 15 or 20 of them.

Towards the end of the first lap, a motorcycle flew by, kicking up dust. He yelled something unintelligible at us, and I think it included the word “left.”

Moments later, a tall, dark Kenyan sprinted by on my left. It took me a second to realize that yes, in fact, at the 11k mark I was being lapped.

I moved over to the left – all the other runners were there, and it seemed like the fast ones would be passing on the right, like I had figured out earlier. Within a few minutes, three or four more Kenyans passed me. I cheered for them, but they didn’t spare a fraction of a calorie to acknowledge it. They were so focused on the race.

For Kenyans, a race like this can make or break a career. There are entire colonies of Kenyan runners training for a day like today. Any mistakes so close to the finish line can change the course of their lives and the lives of their family. Because there is so much running talent in Kenya, second really is the first loser.

It was okay that they didn’t respond to our encouragement.

I turned off for the second lap, and suddenly everything was quiet. The marathoners were alone.

The most surreal part of the race was crossing under the start line a second time. Two hours ago, the place had been exploding with energy and excitement. Thousands of people were there to run or to spectate or to help organize.

This time, I was the only runner. There was one security guard lounging on a picnic table. He may have looked up as I trotted across under the green “Start” banner, contemplating the fact that I was only halfway done and had a lot more work to do. The hard part was just beginning, and only that security guard was there to see it.

So far, there was no knee pain. But my back and shoulders were cramping up, something I’d never experienced before. Most likely this was due to a lack of running-specific training. It was a struggle to stand up straight.

Sometime around the first hill, I fell into step with a Kenyan girl wearing bright pink. I think she was much younger than I. Her grasp on English was tenuous, but she did share her name: Esther.

I’ve written about this before, but it’s still so powerful; running has a way of bringing people together, despite all sorts of differences. We didn’t even share a common language, but we paced off each other for a good 5k, struggling up hills and breathing hard. In the face of adversity, we came together to support each other. We knew what the other was feeling, and we knew we could help each other.

We eventually parted ways; she pulled away after a few kilometers. I’m pretty sure it was because she was a Kenyan, and Kenyans are fast.

I swear that the second lap had more hills than the first. I know that isn’t possible, as we were running the exact same course. But this time, the hills seemed much longer and steeper. Also, where were the downhills?

For several kilometers after Esther and I parted ways, I was alone. Tall, golden grass stretched as far as the eye could see. White clouds spotted a blue sky, and the only sounds were the rustling of the grass, my footfalls on the dirt, and my heavy breath. There’s something peaceful and reassuring about being alone on a run. While the energy of the first lap was fun and exciting, there’s a familiarity about running alone. It’s something runners do all the time. It’s something we know how to do. Being able to draw on that knowledge and experience is reassuring, especially during the second half of a race.

I was struggling. It was getting hot. I felt slow, and was moving slowly. My back and shoulders were hurting, and my legs felt heavy. About the only thing that didn’t hurt, paradoxically, was my knee.

I sang the Kenyan running song to myself, which I’d learned earlier in the week while training with a Kenyan runner.

The song goes:

Pole Pole

Mos Mos

Haraka Haraka

Haina Baraka

Which roughly translates to “Slow slow, speed has no place here.” This was never more true than now, I thought to myself.

I compromised with a run-walk combination, but sometimes, my mind would say “run,” and my body would just not do it, slowing to a walk despite my best intentions.

The dust on the course was coating the inside of my mouth with a thin grit. I was drinking about a quarter of a liter of water every 2.5k to help clear it out. I still felt dehydrated.

A helicopter flew overhead, and I waved, as I had for previous helicopters. I didn’t know if he could see me, but sometimes it’s more the act of interacting with another human that’s the motivating factor, rather than the person’s response.

The helicopter, uncharacteristically, didn’t fly away. It started making circles overhead, disappearing behind a hill to reappear moments later. I wondered if he was scaring an animal off the course and if I should be running faster to escape the animal. I tried to use that to encourage myself to run faster. Nothing changed; I kept plodding along.

I learned later there was a pair of black rhinos just ten feet off of the path, somewhere ahead of me. The helicopter was swooping down to scare them off. I didn’t see them, so either the helicopter pilot did a great job or I just wasn’t very alert. Either was equally possible at this point

Last week in Tanzania, we returned from an evening game drive. Another group, also out that evening, showed us an amazing video they had taken that day of a wildebeest. Wildebeest are very stupid and also nearsighted. This one was wandering around, and, caught on camera, walked within ten feet of a lion. The lion was staring right at it, crouching in the grass. Once the wildebeest had passed on, the lion pounced. It was over in moments. The wildebeest hung by the neck from the lion’s mouth, while the lion waiting patiently for the life to drain out of its prey.

As I was running, I kept thinking of this stupid and nearsighted wildebeest. That wildebeest and I had a lot in common this day. This far into a race, common sense starts to go, and, without my glasses, I couldn’t see very far. There could be a lion just feet away from me, lying in the grass, waiting for a weak, depleted human prey to run by.

There was nothing else to do but keep running. If a lion was waiting, there was really nothing I’d be able to do to fend it off. It could certainly outrun me. I may as well keep moving.

With around 10k to go, the trail started descending. I ran most of the downhill, albeit very slowly. I promised myself I’d run in earnest around 5k, but when that signpost came and went, I was still mostly walking.

I promised myself I’d run the last 3k for sure, but that signpost came and went as well. Finally, with 1k to go, I picked it up and ran in earnest … which, by now, meant about 14 minute miles. When the “500 meters to go” sign appeared, I knew I could at least run that, and came in very slowly to the finish.

Other than the back and shoulders, I felt okay – no major pain. I made my way to the massage tent to take care of those tight points, and a few minutes later, the pain there was gone.

I will say, at no point during the race did I feel like a Kenyan. I felt more like an elephant – slow and lumbering. I don’t think Kenyans feel slow and lumbering.

My knee felt great. I don’t know how to explain it, but there was absolutely no pain there. It seemed like an impossibility, that I could run a marathon on so little running training, and escape unscathed. I really have no idea how the knee held up. I don’t believe in miracles, but that word crossed my mind after all.

It’s hard to explain how difficult the recovery process had been and continues to be. There were many, many times over the last few months where I was sure I’d never run marathons again. Because distance running is so integral to my self-identity, there were some very dark periods in the last few months when I had to soul-search, and really think about who I was as a person.

I’m glad to have been forced into that self-reflection, even though it wasn’t at all fun. I’ve grown a lot, and even though I don’t rely so much on running anymore … well, maybe, after this race, I might be able to run again after all.

Molly, ever intrepid, finished first for girls in our group. She accomplished her goal of running faster than a Kenyan, finishing in five hours and twenty minutes. Despite my struggle, I wasn’t far behind, finishing in five hours and forty eight minutes.

The race was slow for me. Pole Pole. Very slow. But: a finish is a finish. Once you’ve run punishing ultramarathons, the time ceases to matter. All that counts is crossing the finish line.

This was continent number five … up next, Asia?

Edit: If you want 60 written pages about the whole trip, here it is. I processed a lot by writing at this time.

Sounds phenomenal. What an accomplishment. Can’t wait to see photos and hear how many girls ran the marathon in all. Congrats, Lisa!

Great read. Glad you had a great time in Kenya.