- Getting after it on the muddy trails.

I just got back from what can only be described as one of the most epic escapades I’ve been privileged to undertake – a two-week expedition to the loneliest place on earth, where myself and about 150 others explored, adventured, and, of course, ran a marathon.

If the title didn’t give it away, we went to Antarctica.

[Warning – probably a long and rambling post. It was an awesome trip, and the marathon was just a small part of it. It will be hard to do it justice.]

Backstory. I first heard about the Seven Continents Club when I ran the Inca Trail Marathon in 2012. The club is for those who are in the process of running, or have completed, a marathon on every continent. Obviously, the most logistically challenging continent to run a race on is Antarctica. In 2012, I also learned that there’s a 3-5 year wait list to get on a voyage down there, so I put down a small deposit – I figured I’d decide to take that journey if, and when, the time came. Putting down the Antartica Marathon deposit was choosing more of an option to participate rather than a firm commitment to this outrageous expedition.

Since then, I’ve run races on two other continents: Australia and and Africa. Antarctica makes six (although my Europe marathon was a solo, unsupported run, so I’ll probably have to go back and do that one again).

When I finally got off the wait list for Antarctica, the timing couldn’t have been better: it overlapped with my school’s spring break, and I’d get to train through Philly’s miserable winter (that last part turned out to be especially helpful during the race).

Before the race. Two weeks ago, four hundred of us met up in Buenos Aires with our Marathon Tours organizers. We divided into two ships: The Akademik Ioffe, which left one day early and whose runners would race on March 9th, and my ship, the Akademik Sergey Vavilov, sister ship to the Ioffe, whose runners would race on March 10th. The results from the two days would be aggregated (important for later).

We had a few days in Buenos Aires – padding for those whose flights had been delayed – and a small group of us visited Colonia del Sacramento, Uruguay for a day. That trip led to some shenanigans, such as a 20k training run in Uruguay which was actually only 1.5k. This silliness quickly solidified the friendship of this group of 9, and we affectionally named ourselves “The Colonials.”

That day in Uruguay foreshadowed the depth of some of the friendships that would form over the course of the trip. Runners are a strange bunch, but there are some deep commonalities we have which makes it easy, and rewarding, to become fast friends with fellow running travelers.

The first two days were spent crossing the infamous Drake Passage. Many of us, myself included, spent significant time in our bunks attempting to avoid seasickness, with mixed success. We spent the time in-between getting to know each other, taking photos of the open ocean, and attending lectures on everything Antarctic, from penguins, to whales, to ice.

There was more than a little nervous energy onboard. Everyone was thinking about the race, and that manifested itself in a variety of ways. Most notably, we discussed every single aspect of the day-of race logistics ad nauseam. A couple of components were just unique enough that they made for interesting talking points. For example, we had to provide all of our own food and water during the race, and nothing could have a wrapper. Traditional food items, like Clif bars and Gus, were ruled out. Everyone had their own workaround, and we heard about all of them. I planned to use unwrapped Snickers bars shoved into a front pocket, operating under the assumption that they wouldn’t melt due to the frigid temperatures.

I was also not 100% convinced we’d even be running the race at all, so I was trying to avoid getting my hopes up too much. The entire lead up to the race was filled with weather warnings – inclement weather could cancel the race completely, and, in Antarctica, weather is not something you gamble with. I’d been reading the Ernest Shackleton story in my spare time, and, based on his harrowing 17-month survival experience stranded on the continent, I was more than convinced that the race should be called off in the case of poor weather. Nobody wants to get stuck ashore in Antarctica and forced to eat dog pemmican.

However, our first day ashore in Antartica – the day before the race – was amazing. We visited Half Moon Island, known for its fur seals and chinstrap penguins. There’s also one, lone macaroni penguin – named Kenneth – who thinks he’s part of the chinstrap colony. The island itself was stunning – a little, white crescent surrounded by pounding, grey waves. It was our first taste of what Antarctic isolation is really about.

That day, the runners on the Ioffe were running their race. We learned that part of the course was drowned under about a foot of water due to melted snow, so they’d had to re-route, but they’d all made it safely back to the boat after running. That night, after our pre-race briefing, I removed myself from the rabble and anxiety – I didn’t want to discuss race-day nutrition for the 800th time – and went to bed early.

The race.

I woke up multiple times during the night. Just outside the porthole, massive snow flurries blinked in the dim deck lights. I kept trying to convince myself that it definitely wasn’t snow, but every time I woke up, it was definitely still snow, and it was piling up on the deck railings.

By the time we made our way to breakfast, it had stopped snowing, although the winds were holding steady at about 30 knots, with gusts to 35 knots. Even as we packed our dry-bags with warm clothes, filled up our water bottles, and donned our foul-weather gear for the boat ride over, I still wasn’t convinced they weren’t going to call it off due to weather.

We were aiming for a 9am start, which meant we had to start offloading 100 runners around 8am. Many of the Colonials were in a later boat – second or third-to-last. It seemed prudent not to wait in the cold for an hour.

The boats – called Zodiacs – were little rubber contraptions. During any expedition away from our ship, even if it was a very short trip to shore, each Zodiac carried ample extra fuel, enough food for all ~12 passengers for three days, and basic shelter supplies. We all wore lifejackets and waterproof foul-weather-gear at all times when on the Zodiacs. Again, no messing around down here.

On the boat ahead of us, a group of runners, including a family, were navigating the gangway down to a Zodiac. One woman was extremely terrified to step off of the ship and onto the gangway, which was shaking rather violently. She let her son and daughter escort her slowly down to the Zodiac, but the Zodiac was pitching and rolling on the choppy swells. I saw her reach a shaking hand out to cross from the gangway to the Zodiac, but she couldn’t take that step across onto the boat. She turned around and came back onboard the Vavilov. The Zodiac finished loading – without her – and took off for shore. (I found out later that she gave it another go, made it to shore, and finished the half marathon. The whole trip was full of inspirational stories like this).

Our trip over on the Zodiac took about 15 minutes, and the winds were fierce. We huddled together on the rubber seats, and I rubbed strategically-placed hand warmers to keep my fingers mobile. We all hoped that when we started moving, we’d warm up.

When we got to shore, we jumped out of the boat and into the freezing water, feet protected by rubber boots. We waded to shore and then up to the start line.

Even then, divesting of our foul-weather gear, we were still debating how many layers we should wear. I opted to trust my Philly training, and stripped down to just three layers: a long-sleeve shirt, a short-sleeve shirt, and a light jacket. I also had on running tights, a neck buff, a baseball-like hat to protect from any possible precipitation, a headband for ear warmth, and a warmer hat on top of that. I wore heavy ski gloves on my hands and tucked hand warmers into each one, and my normal trail shoes on my feet.

The start was anticlimactic (and I have never seen so many GoPros – mine included – recording it). Thom, our intrepid race director, counted us down from five, and we started trotting down the muddy course.

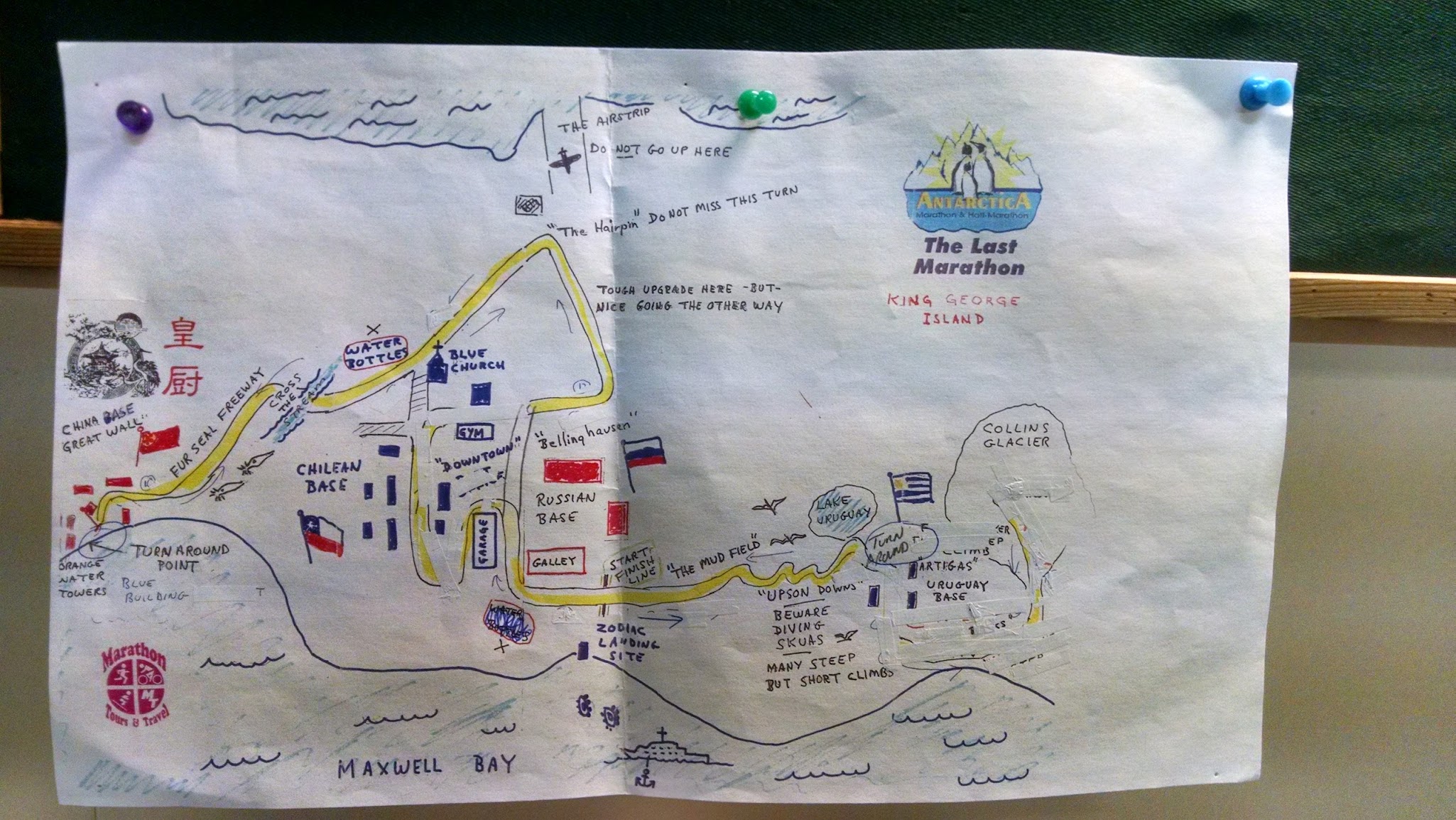

The course would be a six-loop out-and-back course. Basically, we’d run 2.18 miles to a turn-around, then run back to the start, and do that six times. I tend to like loop courses, and I think this is because my powers of observation are pretty weak during a race – I’m discovering something new on every lap.

The first lap or two felt easy. The scenery was gorgeous at parts – the first mile or so was through the Russian and Chilean research bases, and after that we passed a glacial lake and ran right near the shore of the island, until we turned around at a Chinese research base. Despite how windy and overcast it was, it was very cool to be running past these towering mountains – in Antarctica!

I was powering up the hills and keeping pace with some runners that looked pretty fast to me. I didn’t think I had a chance of placing, but I do like to count how far back I am from the lead women … and after the first lap, there were only four women in front of me. My roommate, Erin, was in 3rd, and in 4th was another girl from Philly, named Taylor.

I was pretty sure I’d hit a wall at some point and fall back, so I didn’t think too much about it. However, at the end of lap 2, I was feeling pretty good – I’d been pacing off of another runner, and at the turn-around, he took a bit longer at the aid station than I did, so I kept going. The runner in 2nd had fallen back, which meant Erin was in 2nd now. Taylor, in 3rd, was just ahead of me … so I kept trotting along.

Even though I was keeping an eye on the competition, I, like most runners, was really just in it to finish. Because all of the runners knew each other by this point, the cheering throughout our short course was so enthusiastic and genuine. The course was only a few miles, so we saw our new friends frequently, and we all took the opportunity to encourage each other loudly, to the amusement of on-base researchers. They looked at us with what I like to imagine was admiration, but more likely confusion and worry for these crazy people who’d be out in these conditions.

Every so often, I would just appreciate how ludicrous the whole construct was – running a marathon on Antarctica is pretty crazy, when considered in the absolute. In my running career, it was also the race that I’d been thinking about for the longest – three years is a serious chunk of time, and this race was the culmination of that preparation.

Around lap 4, I was feeling a little fatigued, but Taylor was still just ahead, so I kept pushing. I passed her at one point, but then she passed me back, and I was pretty sure that was the end of things. It didn’t matter anyway – there was no way that, after combining our times with the other boat’s, the third-place person on our boat would also place overall.

However, I then passed her again, and with only 10k to go, I felt like I could maybe push it to the end and finish 3rd on my boat.

The next six miles were a slog. The hills were starting to feel steeper than before, and there were two short ones that I would walk for a quick recovery. The weather had also taken a turn for the worse, and it seemed like, no matter which direction we were heading, we were facing a stiff headwind. It had also started sleeting, and little particles of ice were now driving into any unexposed skin. I moved my buff up to cover my nose and mouth, but all that did was restrict my breathing, so I left it around my neck and faced the storm.

The last lap was rough. At the turnaround, with only 2 miles to go, I had my GoPro running. I crouched down to show off my favorite race sign – it said “Penguin Crossing” – and saw my Philly compatriot right behind me. I kicked it into gear and didn’t look back.

I felt like I was flying through the last two miles, although I’m sure it looked more like a limping slog than an Olympic sprint.

The last 0.2 miles were up a shallow hill. I saw the 26-mile marker, and for some reason, turned around – I think I didn’t want to get passed at the last second. Taylor was right behind me! I turned back and sprinted to the finish line. She came in just a few seconds after me.

We high-fived and hugged it out, taking a finish-line photo (with Erin, who had finished 2nd and about 20 minutes ahead of Taylor and I. The first-place woman had already gotten back on a Zodiac and was headed for a hot shower). Taylor and I agreed that there was no way we’d be in contention for an overall podium spot, but we appreciated the competition.

Volunteers bundled us into our foul-weather gear and back onto a Zodiac before we knew what was happening. My fingers, warm throughout the race, immediately became numb when I started handling zippers and velcro, and the Zodiac ride was pretty rough as a result.

After the race. That night, we learned that our boat had dominated the rankings. The men on Vavilov swept the top three spots, and the woman had grabbed the top two … and maybe the third! For the next twelve hours, I was constantly checking to see if they’d posted the results … and found out that a girl on the other boat beat me by two minutes. Very disappointing. I like to think that they had easier weather – it was very sunny! – but I know she also ran a great race.

The next several days were a combination of calm appreciation of our success and evening parties of wild, reckless abandon. Days ashore were happier and more relaxed. A few highlights:

- A double-rainbow over icebergs.

- Quiet kayaking on reflective water (after a messy capsize due to inclement weather the day before).

- Whale watching – literally 20 feet from our boat – in the calm waters of Wilhelmina Bay on the last day.

Epilogue. The whole experience was amazing. I focused here on the race because this is a blog about running, although, as mentioned, the race just became one part of a much broader, more epic adventure, which really deserves its own blog. Just like summer camp, we made memories and forged friendships that we’ll remember for a lifetime.

Antarctica is a pristine, unspoiled place. It is stark and isolated, and unlike anywhere else on earth. I am grateful that humanity was only able to reach it after developing an appreciation for preserving natural beauty – the continent is governed by a multinational research treaty – although I fear for the day that the lucrativeness of mineral rights overshadows this agreement.

The staff concluded our voyage with this quote:

Out here is where the magic happens, here in the quiet hills.

Here is where you have cried out with moans as deep as the earth.

Here is where you have found your long lost self that the madness took away.

So when you get back to those who talk loud in small rooms,

Remember that you have been to a place too beautiful for words.-Anonymous

Here’s to the adventurers.

Want more Antarctica marathon?

8 Comments