The Inca Trail is 32k and ends in Machu Picchu. It starts at 9,000 feet and peaks around 13,800 feet above sea level. Most people hike it in four days.

The Inca Trail Marathon ins a 42k course. It’s run on the same trail and also ends in Machu Picchu. 42 competitors attempted to run it in less than a day.

For the last week or so, I’ve been traveling around Peru, prepping for the first annual Inca Trail Marathon. The race is the first marathon-length race that includes the Inca Trail, so in a lot of ways, this was a pretty big deal.

On the way to the start of the race – I’m on the left

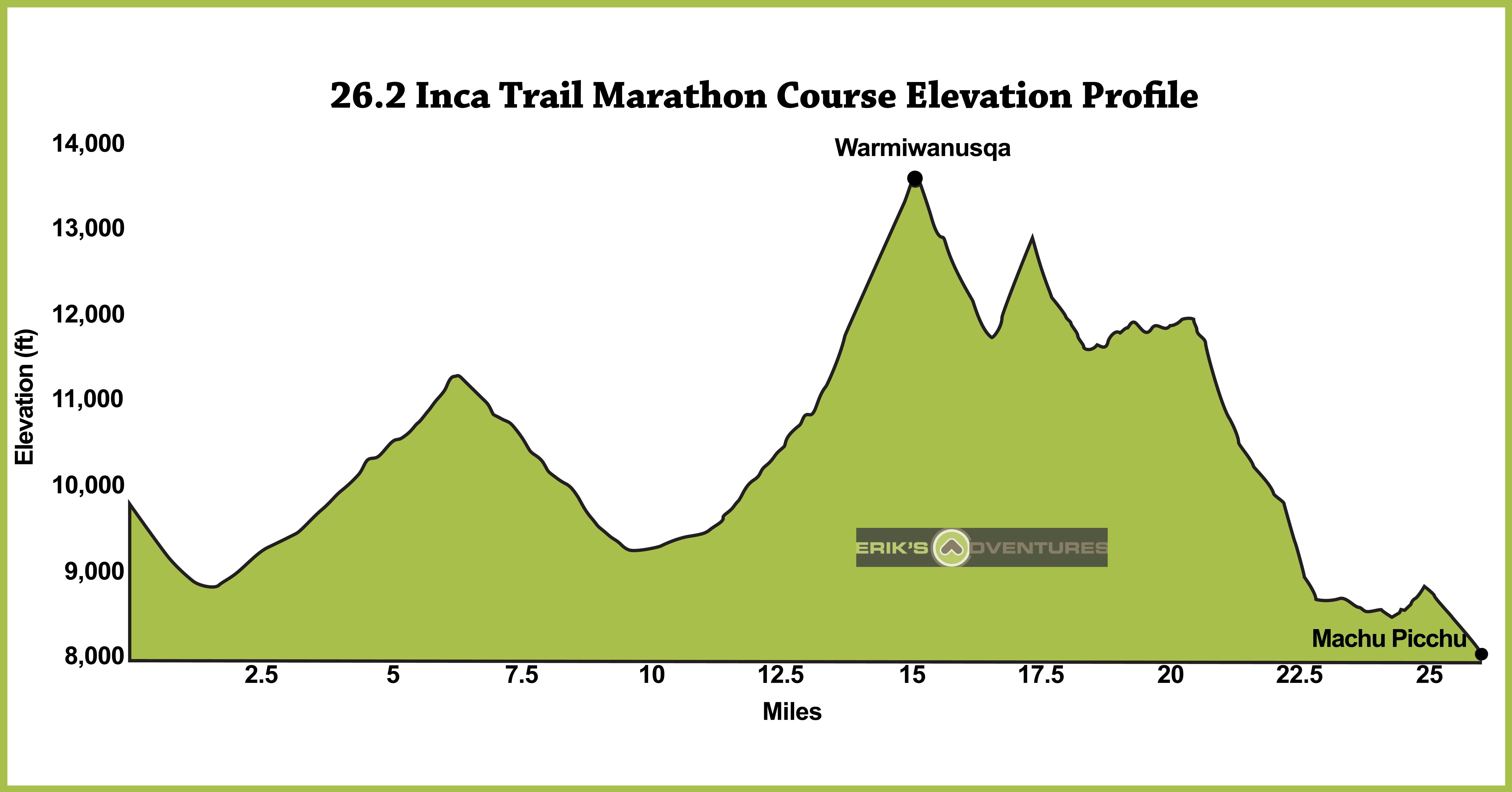

The race is 26.2 miles [obviously]. It starts at KM 88 of the Inca Trail, which is about 8,500 feet above sea level. It peaks at Dead Woman’s Pass – Warmiwanusqa – around 13,800 feet, then plunges quickly to 11,800 feet, then quickly back up to 13,000 feet. After that it’s basically downhill to the finish – around 8,000 feet.

The race started yesterday morning, and it was substantially more difficult than any of us anticipated.

The first few miles were on some out-and-back dirt trails, which gave all of us plenty of confidence that we could finish the 26.2-mile race that day – the cutoff time was 11 hours, because the checkout into Machu Picchu closes at 4:00. In addition to some fairly straightforward trails, the 8,500-foot start seemed pretty easy since we’d spent the last three or four days to train in Cusco, which is at about 11,200 feet of elevation.

Around mile 8, the course started gently climbing. [Note: the profile below is sort of wrong- shift everything right about four miles]. The race still didn’t seem unmanageable; I was easily chatting with one of the Inca Trail porters. The Inca Trail porters are the equivalent of Everest Sherpas – they carry gear for hikers. [Amusing sidetone: he asked where I worked, and I said “Google” – he hadn’t heard of it.]

Around mile 12, the real climbing kicked in. Between mile 12 and 15, we gained close to a mile of elevation. Not only was the oxygen swiftly thinning as we ascended, but the trail suddenly became very technical. We were climbing steep, jagged, irregular stone steps for essentially three vertical miles. Each step felt like its own mountain, and each took a Herculean effort to surmount.

It took more emotional strength than physical strength to climb that portion of the trail. Every time the trail went around a corner, another set of steps would, depressingly, come into view. Towards the top, I was exhausted and demoralized. At that point, I was taking twenty steps, then stopping and sitting down for ten seconds. Then twenty more steps, then sitting down for ten seconds. Repeat for what seemed like forever.

On the plus side, the sitting down allowed for a chance to look at the gorgeous scenery. The first part of the ascent was through what one runner called an “Enchanted Forest,” with a river on one side of the trail and jungle vines framing the path ahead. The higher we went, the more beautiful the view became. Once I passed the tree-line, the mountains came into view. The Andes are just as steep and profound as they look in pictures.

Around mile 15.1, I reached the top of Dead Woman’s Pass, the highest part of the course. It was pretty clear at this point that most of us weren’t going to make the cutoff at mile 22. We needed to do another 7 miles in about two hours. On any other course, that would have been laughably easy, and part of me still thought it was possible.

At Dead Woman’s Pass, I was cautiously optimistic that I could make the cutoff, because I knew there would be some downhill before the next major climb. This was going to be a great opportunity to pick up some lost time and let gravity do some of the work for me.

It turns out that the other side of Dead Woman’s Pass is just as terrifying as the first side. Remember those steep, jagged, irregular stone steps? They’re as impossible to run down as they are to run up. The next mile or so turned into a series of single, cautious steps down, again, and again, and again. This was mostly frustrating because, physically, I was ready to push it and fly down a major hill. The difficult terrain was definitely preventing that. It quickly became clear that the cutoff would be far outside of my reach.

Instead of focusing on the lost downhill, I set my sights on the aid station at mile 16. Due to a questionable vegetarian lunch the day before, I’d contracted a nasty case of food poisoning, which effectively meant I had started the race having not eaten anything for the prior 24 hours. Given that, I was hoping for some sort of protein bar or something to replenish my severe lack of calories.

Given those expectations, the aid station was disappointing. They didn’t have water [only Gatorade?], and they had some strange granola bars, chocolate, and not-very-salty pretzels.

On to the next climb, then.

The next climb was only about a mile, and was just as steep as the first one. This was a little less difficult, because I knew it wouldn’t peak as high as Dead Woman’s Pass.

About 3/4 of the way up the second climb, it started to drizzle.

On the way down from the second climb, it started to rain. This meant that instead of stepping down steep, jagged, irregular stone steps, I was navigating down steep, jagged, irregular stone steps effectively covered in vaseline.

The course flattened out a bit, but the stones didn’t go away. At this point, it started to hail.

When the lightening and thunder started, it occurred to me that there was probably a reason this section of the course was called “Cloud Forest.”

Around mile 19, I was getting a bit nervous. I hadn’t actually seen anybody for quite some time. There were no other runners near me, and I hadn’t seen any race porters or other hikers. With each passing step, I was increasingly convinced I had taken a wrong turn somewhere. Should I go back and look for another runner, or continue on and hope I’d find another aid station? Or if not another aid station, at least a random local house where I could spend the night? I fortunately had my cell phone, passport, 10 units of local currency, and credit card, so theoretically I could get home from anywhere, if the need arose.

At mile 20.5, I topped another peak and found what I thought was an aid station. It really only had Gatorade, and there was no race official nearby. The rain and hail had somewhat subsided and turned into a mist, and through the fog I could see several tents that other hikers had set up for the night.

I tried to use my Spanish to ask a nearby group if they’d seen anyone with a yellow bib. Unfortunately, they spoke Chinese.

A few moments later, the race official came running out of the mist and pointed me in the right direction. I asked him how many minutes to Winay Wayna, the aid station at mile 22 and where I would be camping that night. He said about 30. That seemed reasonable for a mile and a half of descent.

After leaving the pseudo-aid station, I immediately got lost in some ancient Incan ruins. Any other time, that would have been pretty neat; who doesn’t want to explore really old pre-colonial ruins? The combination of rain, exhaustion, and really difficult trails made an impromptu explorations somewhat less exciting.

About ten minutes after I left the aid station and regained the trail, I encountered another porter with a group of hikers. In Spanish, I asked him how far it was to Winay Wayna. He said about 40 minutes. So, I estimated it was somewhere between 10 and 40 minutes, based on what he and the race porter had said. Fine – at least we had a range to work with.

In Turn Right at Machu Picchu, author Mark Adams introduces the concept of Peruvian Standard Time, which is a kind way of saying that Peruvians have a very lackadaisicalapproach to time. In the book, Adams goes to visit a friend of his, and someone nearby says the friend will be back in 10 minutes. Adams later learns the friend wouldn’t have been back for another week.

About 30 minutes after I left the aid station, I ran into a race official. He pointed me down the correct path, and I asked him how far it was to Winay Wayna. He said probably another 40 minutes.

At this point, the sun was probably starting to set. That is to say, the mist and fog was turning a slightly darker shade of grey. I was very concerned that I would be still on the trail while it was dark. I’d been on the course for somewhere around ten and a half hours.

A few minutes later, I came upon a pair of other racers. This was such a motivation; as any ultrarunner knows, sometimes just having someone to talk with can ease the race tension and take your mind off of the difficulties of the race. I stuck with a woman I learned was named Jenny, and we continued to make our way down the slick stone steps in the gathering darkness.

I later learned that Jenny had done several races that take place over the course of multiple stages; competitors run for a bunch of miles, then camp out somewhere, then run a bunch of miles the next day, and camp again. She’d done a few that were five or seven days of this, so it turns out that she was very prepared for the overnight camping eventuality. Definitely a good person to have met right before an unexpected overnight camping.

As the light faded, we were both very worried. Out of the 42 runners, there were easily 15 or 20 behind us who were still on the trail. They would have to hike the steep, jagged, irregular, vaseline-covered stone steps … in the dark. With no headlamp, because none of the racers thought they’d actually be out past sunset.

We met a group of race officials a few minutes later, and one turned around to escort us down to the camp. The other three porters continued on to find the remaining runners who were still on the course. We asked our guide how long it would be until we reached Winay Wayna. He said 20 minutes. Jenny snorted, and said that probably meant an hour in real-person time.

About 45 minutes after we encountered the porter, we rolled into camp. [For reference: it was about an hour and a half since we’d left the previous aid station]

The camp was cold, dark, and wet. I had a spare shirt and pants in my drop bag, but no extra jacket. Jenny and I skipped dinner and went straight to sleep.

It was a long night. I woke up several times, partly due to a general inability to sleep, partly because my stomach was very unsettled, and partly because I didn’t know if the other runners behind us were safe.

Breakfast the next morning was a sardonic affair. When your body is in such a state of shock, the only reaction is gently sarcastic amusement. We made choices between the spoon that fell on the ground and the one that fell in the rice pudding. I wore the sleeping bag to the food tent in lieu of a jacket.

At breakfast, we learned that only 12 out of the 42 runners had made it to Machu Picchu before the cutoff. 15 of us were at Winay Wayna. That meant there were still 25 people on the course behind us, camping at sites that hadn’t been intended for racers to camp at. We gathered that everyone was accounted for, which was a relief.

Around 6:30 am, the 15 of us left camp to finish the next few miles to Machu Picchu.

Caesar, who had been one of our tour guides this week, led the way. He and I chatted in Spanish about a variety of topics, including his education; apparently it takes five years of studying to become a tour guide in Peru.

From Winay Wayna, e had about 6k to go. None of us were running. There was a sense of camaraderie amongst the group; we’d spent the night together, and it was clear that nobody was competing for time anymore. There was a shared sense of suffering that even the smell of the finish line couldn’t erase.

After a bi of walking, we rounded a corner. Caesar pointed to a set of about 50 very steep steps. “These are the Monkey Steps,” he explained. “You can use your hands – like a ladder.” Apparently, this particular staircase is also colloquially known as the “Gringo Killer.” Caesar promised these would be the last upward steps we would have to attack.

That last challenge was worth it. At the top, we reached the Sun Gate (Intipunku, in the local language Quechua). From there, we got our first view of Machu Picchu.

This was the part where the overnight camping really paid off. The sun was just up, and it was still early enough in the day that the fog hadn’t moved in. We had a crystal clear view of the most classically photographed angle of Machu Picchu. The sheer effort of the past 26 hours, combined with the exhaustion and the beautiful view, may have caused me to mist up just a bit.

It was all downhill from there – and, for the first time, that was a good thing. The trail finished with a gentle, easy descent for another 45 minutes, ending in the Machu Picchu ruins. A shuttle ride later (and a trip through every room in the hotel, and a short walk to another hotel – to find my misplaced luggage), I was relaxing in a hot shower.

Overall, this was a pretty hard race. I don’t think I’ve ever competed in a race this difficult. Between the altitude, the elevation change, the terrain, the lack of food, the questionable aid stations, the rain, the hail, and the camping, I would say this was the definition of an adventure race.

I’m happy to have finished, and think I could have probably finished in one day if it weren’t for the lack of calories and the fact that the Machu Picchu gate closes early. I definitely could have run another 5k last night.

Also, this is my third continent on which I’ve run a marathon. Up next: probably Australia in September.

Some athletes!

If you want to check it out, Erik’s organizing this race again next year – in August. The website with additional information is here. This was my first group tour, and I really recommend Erik’s group – really well organized, and some really fun activities leading up to the race (whitewater rafting, hiking, exploring ruins, etc). Excellent for athletes. :o)

Lisa’s epilogue, added in early 2020: After re-reading this race report, I realized I left quite a bit of context out. For example:

- This race was one part of a fantastic week exploring Peru. We spent time in Lima, Cusco, and Machu Picchu, as well as a number of amazing ruins nearby. We took sketchy busses along unpaved roads and ate at questionable roadside cafes. We saw nature and experienced culture. It was really an incredible trip.

- To get to the start of the race, we had to hike in about 10 kilometers to a camp site. This was a really fun part of the trip, because we were all really excited to run, and we got to preview what the course terrain would look like. The night before, we all camped out in tents under the stars – it was absolutely magical.

- The night before the race, I also got violent food poisoning. I am not sure why I didn’t write about that in this race report, because it really determined the outcome of the race – e.g. that I didn’t finish it the first day. The night before, I was waking up in the middle of the night to throw up outside the tent, which meant that I got very little sleep and had very little nutrition in my system. The aid stations were WONDERFUL, but mostly food that I didn’t feel like I could eat. When I finished the race, I immediately went back to the hotel, showered, and tried to sleep – with mixed success, since I was mostly throwing up. When we got back to Cusco, I did something very embarrassing – I went to a Starbucks. They had food I thought I could keep down (e.g. that was familiar to my stomach). I also remember getting an entire tube of Pringles and demolishing it.

- I met up with this group of friends again at CIM later that year, and it was a really fun reunion. Most of us have since fallen out of touch, but getting to go on this trip with such amazing runners – and humans – was a real treasure.

Amazing – you should be so proud! Love the diagram too haha.

Meanwhile – http://www.sydneyrunningfestival.com.au/enter/marathon

That’s the one I want to do! =D

Plannnig to hike this trail next summer! Can’t even imagine running a marathon on it!

You actually ran into Jenny Hadfield from Runners World! You were indeed BLESSED!